Special File Permissions of SUID GUID and Sticky Bit

Overview

You see an s instead of x in the file permissions? Linux has some special file permissions called SUID, GUID and Sticky Bit. Know more about them.

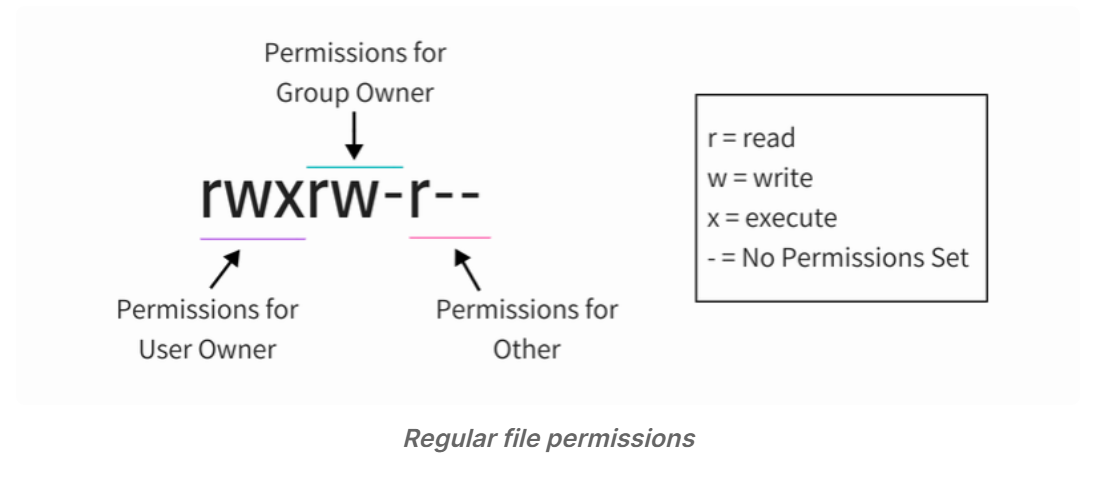

File permissions and ownership are the basic and yet essential security concept in Linux. You probably are already familiar with these terms already. It typically looks like this:

Apart from these regular permissions, there are a few special file permissions and not many Linux users are aware of it.

To start talking about of special permissions, I am going to presume that you have some knowledge of the basic file permissions. If not, please read our excellent guide explaining Linux file permission.

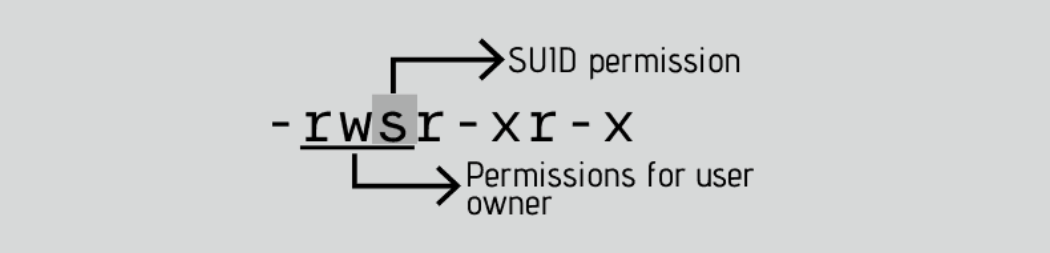

Now I’m gonna show you some special permissions with new letters on Linux file system.

In this example, the passwd command, responsible to change the password of a user, has the letter s on the same place we expect to see x or -, for user permissions. It’s important to notice that this file belongs to root user and root group.

With this permission you don’t need to give sudo access to a specific user when you want him to run some root script.

What is SUID?

When the SUID bit is set on an executable file, this means that the file will be executed with the same permissions as the owner of the executable file.

Let’s take a practical example. If you look at the binary executable file of the passwd command, it has the SUID bit set.

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -l /usr/bin/passwd |

This means that any user running the passwd command will be running it with the same permission as root.

What’s the benefit? The passwd command needs to edit files like /etc/passwd, /etc/shadow to change the password. These files are owned by root and can only be modified by root. But thanks to the setuid flag (SUID bit), a regular user will also be able to modify these files (that are owned by root) and change his/her password.

This is the reason why you can use the passwd command to change your own password despite of the fact that the files this command modifies are owned by root.

Why can a normal user not change the password of other users?

Note that a normal user can’t change passwords for other users, only for himself/herself. But why? If you can run the passwd command as a regular user with the same permissions as root and modify the files like /etc/passwd, why can you not change the password of other users?

If you check the code for the passwd command, you’ll find that it checks the UID of the user whose password is being modified with the UID of the user that ran the command. If it doesn’t match and if the command wasn’t run by root, it throws an error.

The setuid/SUID concept is tricky and should be used with utmost cautious otherwise you’ll leave security gaps in your system. It’s an essential security concept and many commands (like ping command) and programs (like sudo) utilize it.

Now that you understand the concept SUID, let’s see how to set the SUID bit.

How to set SUID bit?

I find the symbolic way easier while setting SUID bit. You can use the chmod command in this way:

1 | chmod u+s file_name |

Here’s an example:

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -l test.txt |

You can also use the numeric way. You just need to add a fourth digit to the normal permissions. The octal number used to set SUID is always 4.

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -l test2.txt |

How to remove SUID?

You can use either the symbolic mode in chmod command like this:

1 | chmod u-s test.txt |

Or, use the numeric way with 0 instead of 4 with the permissions you want to set:

1 | chmod 0766 test2.txt |

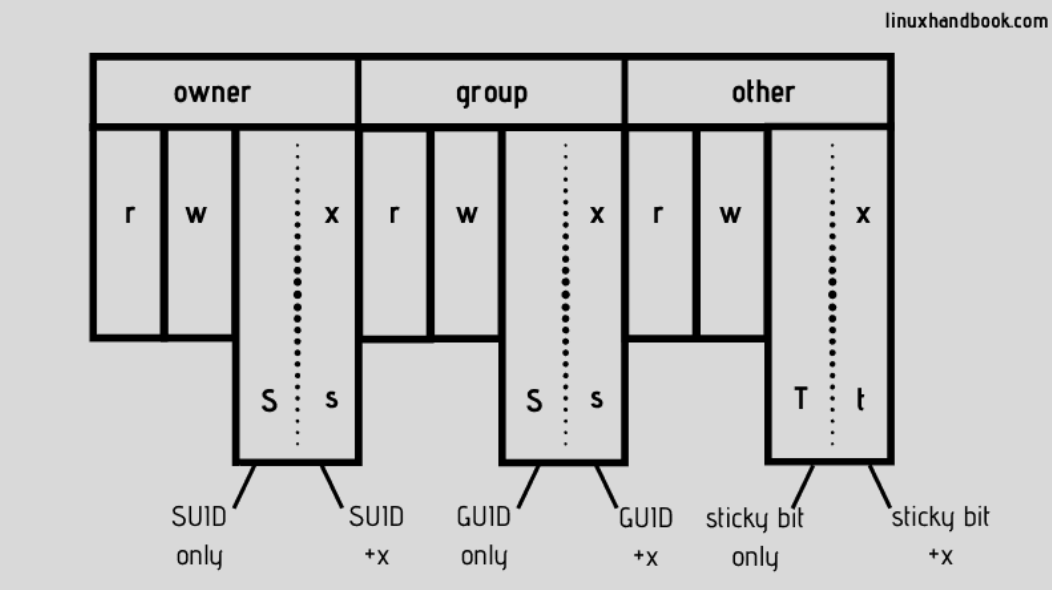

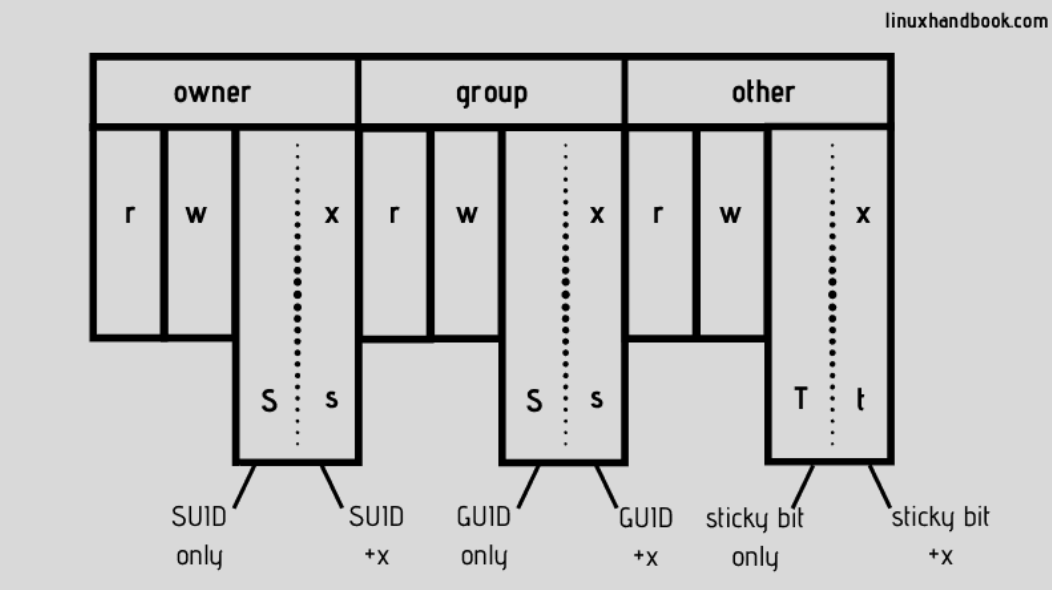

Difference between small s and capital S as SUID bit

Remember the definition of SUID? It allows a file to be executed with the same permissions as the owner of the file.

But what if the file doesn’t have execute bit set in the first place? Like this:

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -l test.txt |

If you set the SUID bit, it will show a capital S, not small s:

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ chmod u+s test.txt |

The S as SUID flag means there is an error that you should look into. You want the file to be executed with the same permission as the owner but there is no executable permission on the file. Which means that not even the owner is allowed to execute the file and if file cannot be executed, you won’t get the permission as the owner. This fails the entire point of setting the SUID bit.

How to find all files with SUID set?

If you want to search files with this permission, use find command in the terminal with option -perm.

1 | find / -perm /4000 |

What is SGID?

SGID is similar to SUID. With the SGID bit set, any user executing the file will have same permissions as the group owner of the file.

It’s benefit is in handling the directory. When SGID permission is applied to a directory, all sub directories and files created inside this directory will get the same group ownership as main directory (not the group ownership of the user that created the files and directories).

Open your terminal and check the permission on the file /var/local:

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -ld /var/local |

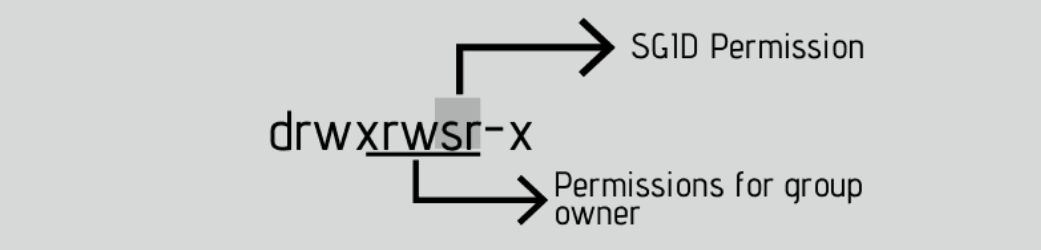

This folder /var/local has the letter ‘s’ on the same place you expect to see ‘x’ or ‘-‘ for group permissions.

A practical example of SGID is with Samba server for sharing files on your local network. It’s guaranteed that all new files will not lose the permissions desired, no matter who created it.

How to set SGID?

You can set the SGID bit in symbolic mode like this:

1 | chmod g+s directory_name |

Here’s an example:

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -ld folder/ |

You may also use the numeric way. You just need to add a fourth digit to the normal permissions. The octal number used to SGID is always 2.

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -ld folder2/ |

How to remove SGID bit?

Just use the -s instead of +s like this:

1 | chmod g-s folder |

Removing SGID is the same as removing SGID. Use the additional 0 before the permissions you want to set:

1 | chmod 0755 folder |

How to find files with SGID set in Linux

To find all the files with SGID bit set, use this command:

1 | find . -perm /2000 |

What is a Sticky Bit?

The sticky bit works on the directory. With sticky bit set on a directory, all the files in the directory can only be deleted or renamed by the file owners only or the root.

This is typically used in the /tmp directory that works as the trash can of temporary files.

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -ld /tmp |

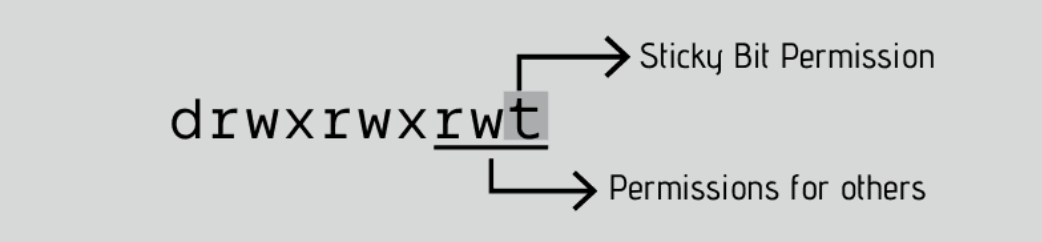

As you can see, the folder /tmp, has the letter *t* on the same place we expect to see x or – for others permissions. This means that a user (except root) cannot delete the temporary files created by other users in the /tmp directory.

How to set the sticky bit?

As always, you can use both symbolic and numeric mode to set the sticky bit in Linux.

1 | chmod +t my_dir |

Here’s an example:

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -ld my_dir/ |

The numeric way is to add a fourth digit to the normal permissions. The octal number used for sticky bit is always 1.

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ ls -ld my_dir/ |

How to remove the sticky bit:

You can use the symbolic mode:

1 | chmod -t my_dir |

Or the numeric mode with 0 before the regular permissions:

1 | chmod 0775 tmp2 |

How to find files with sticky bit set in Linux

This command will return all files/directories in with sticky bit set:

1 | linuxhandbook:~$ find . -perm /1000 |

If the directory doesn’t have the execute permission set for all, setting a sticky bit will result in showing T instead of t. An indication that things are not entirely correct with the sticky bit.

Conclusion

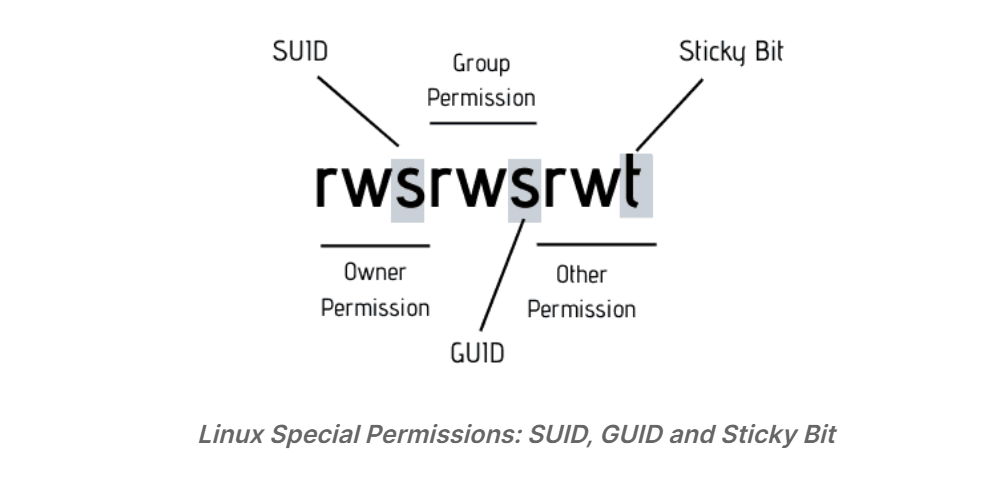

I’ll put this picture here to recall what you have just learned:

This flexibility to manage folders, files and all their permissions are so important in the daily work of a sysadmin. You could see that all those special permissions are not so difficult to understand but it must be used with utmost caution.

I hope this article gave you a good understanding of the SUID, GUID and Sticky Bit in Linux. If you have questions or suggestions, please drop a comment below.